Defending India’s Human Rights Defenders

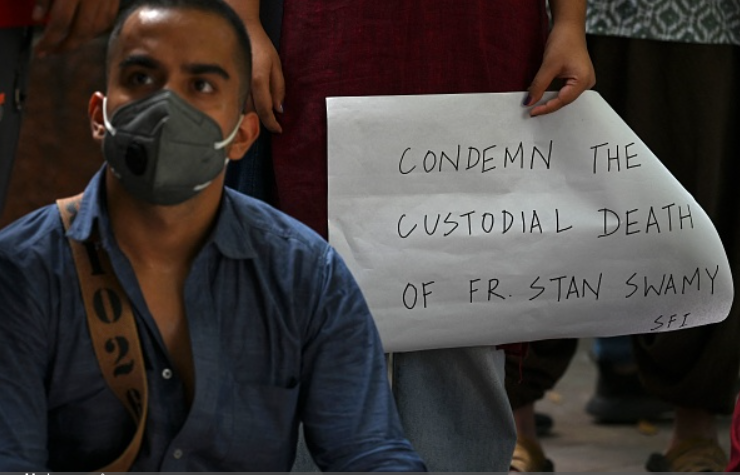

On July 5, 2021, Jesuit Priest and human rights defender Father Stan died in Indian custody at the age of 84. He was the oldest person to be arrested by the Indian government for terrorism. Father Stan’s incarceration led to a global outcry against the Indian government’s brutal treatment of Indian human rights defenders.

Father Stan is one of a mushrooming group of prisoners of conscience whom the Indian government has jailed over the past few years. Using anti-terror laws, including the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) and the recently suspended sedition law, the Indian government has detained critics of Hindu nationalism and transformed political dissidents into national security threats.

India’s persecution of government critics is part of a larger, anti-democratic turn for the Hindu nationalist government. As the space for domestic protest shrinks, governments around the world must denounce the Indian government’s criminalization of political dissident. Formal condemnations, such as Congressman Juan Vargas’s resolution about Father Stan’s arrest, may prompt the Indian judiciary to release prisoners of conscience and unravel a key component of democratic backsliding in India.

Bhima Koregaon and Things to Come

Father Stan is arguably the most famous member of the Bhima Koregaon 16 (BK-16), a group of human rights defenders who have been persecuted for advocating on behalf of India’s Dalit (caste-oppressed) and Adivasi (Indigenous) communities. In 2018, police arrested the BK-16 for supposedly conspiring with Maoist insurgents in Maharashtra to overthrow the Indian government. However, digital forensics investigators reported that hackers with links to local police planted evidence linking the BK-16 to insurgents. Hackers also used Pegasus spyware to monitor the BK-16.

The Indian government arrested the BK-16 under the UAPA, which denies the accused due process. Under the UAPA, judges can deny bail and detain defendants for up to seven years, meaning that the BK-16 have yet to receive a fair and speedy trial. The deadly consequences of this law became clear when Father Stan died in pre-trial detention before he was able to defend himself against these spurious charges. Many of the defendants identified as Dalit, Muslim, or Christian and were targeted for their identities. The BK-16 case is emblematic of the tactics the Indian government uses to silence its critics.

Political Prisoners and Democratic Backsliding

Unfortunately, Father Stan and the BK-16 were the canaries in the coal mine for the Indian government’s treatment of human rights defenders. The Indian government has used existing national security laws, and especially the UAPA, to arrest political dissidents, human rights activists, and journalists, which effectively turns political critics into enemies of the state. As of this year, the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom included 38 Indians in its database of prisoners of conscience—an undercount.

In August 2019, the Indian government revoked Kashmir’s temporary special status in Article 370 of the Indian Constitution and implemented an internet shutdown to mitigate inevitable protests in Kashmir. Since then, the Modi government arrested more than 2,300 people, including journalist Khurram Parvez, under the UAPA, with about 46 percent still in jail as of 2021.

Later in 2019, the Indian government’s brutal crackdown against students who organized anti-Citizenship Amendment Act protests in New Delhi reinforced the Hindu nationalist theme that political dissent is a security threat. The government shut down the internet, used a colonial-era anti-sedition law to prohibit more than four people from gathering, and arrested protest organizers. Yet again, the Indian government used the UAPA to arrest and target Muslim protesters. Through the sedition law and UAPA, the government affirmed its Islamophobic trope that Muslims represent a particular danger to the Hindu nation.

During the coronavirus pandemic, the Indian government used the pandemic to restrict freedom of the press, both directly related to the Indian government’s poor handling of the pandemic and general dissent. The government also used pandemic rules on public gatherings to break up anti-government protests, again in the interest of public safety.

Most recently, Indian police arrested Teesta Setalvad, a celebrated civil rights activist, and former Director General of Gujarat Police RB Sreekumar for their work highlighting then-Chief Minister Narendra Modi’s culpability in the 2002 Gujarat pogroms. Their arrest came after the Indian Supreme Court dismissed a decade-old petition by Setalvad against Modi. They were arrested for allegedly fabricating evidence, which the United States does not dispute and used to implement a visa ban on Modi in the mid-2000s. Setalvad and Sreekumar’s arrests signal a new, more dangerous chapter for civil activists in India, where seeking legal recourse for bad governance is now a form of “anti-India” political dissent.

External Pressure for Internal Change

As the Indian government continues to stifle internal dissent, external pressure may force officials in the Indian government to reverse course. Historically, the Indian government has resisted outside criticisms, but recently, the government responded to boycotts by Gulf States over Islamophobic comments.

Politicians in the United Kingdom, the European Union, Australia, the United States, and the United Nations have expressed concern about India’s prisoners of conscience. These arrests, as some politicians note, are part of India’s increasing political repression at the exact moment when India is gaining geopolitical importance.

There have been some efforts in the United Kingdom. and European Union to denounce Father Stan’s incarceration, but there is no precedent for government institutions issuing formal condemnations of India’s treatment of prisoners of conscience. Most recently, Congressman Juan Vargas introduced a resolution on Father Stan Swamy which would formally denounce India’s treatment of the BK-16 and the arbitrary use of anti-terror laws to arrest political dissidents and human rights defenders. The adopted resolution would provide formal U.S. government pressure on the Indian judiciary to release the remaining defendants and curb the government’s use of the UAPA.

But the U.S. government, which seeks to pull India into multiple multilateral forums, must do more for India’s prisoners of conscience. First, President Joe Biden must designate India as a Country of Particular Concern for religious freedom violations. The Indian government persecutes India’s religious and cultural minorities and punishes those, like Father Stan, who advocate for minorities. The United States should also sanction individuals who have led the persecution of India’s minorities. Both the Trump and Biden administrations have been afraid to take these steps out of fear that strong actions could push India away from multilateral cooperation, especially the Quad.

Despite the deepening U.S.-India relationship, the United States must hold India to account for its human rights violations. If the U.S.-India relationship is meant to rest on shared values of democracy, pluralism, and mutual respect, then the U.S. must honor its commitment to these values.

In his final letter, Father Stan said the BK-16 were not allowed to speak with each other, but he insisted “we will still sing in chorus. A caged bird can still sing.” It’s time for the United States to sing with them.

Image 1: SAJJAD HUSSAIN/AFP via Getty Images

Image 2: T.Narayan/Bloomberg via Getty Images

This article orginally appeared in southasianvoices.org