Faith in Pluralism: Lessons from The Reign of Akbar

By Maryam Moss

Hindu supremacists often link Islam with imperialism by depicting the Mughal Dynasty as one of barbarism and intolerance. Although the modern Hindu right has tried to masquerade criticism of Muslim rulers as anti-colonialist, the overall tolerance of the Mughals remains a focal point during what was a Golden Age for culture in India. In particular, the reforms under emperor Akbar did not create a political upheaval but, conversely, reinforced ties between members of a pluralistic society. Born Jalal ud-Din Akbar in 1542, the unprecedented demise of his father, Humayun, resulted in early ascension to the throne. Strategizing the trademark policies of limited government, justice, and investment in the cultural and religious lives of his subjects, Akbar the Great consolidated an effective administrative unit.

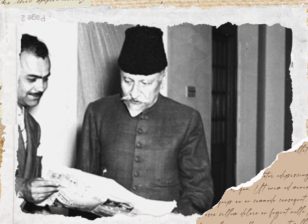

A Profile of Akbar: Insights From a Testimony

c.1605. Photo Source: Wikimedia Commons.

In the year 1578, Father Antonio Monserrate, a missionary of the Society of Jesuits Catholic order, arrived in India. His presence had been requested by Akbar, who was known for convening theological discourses at his palace. Monserrate’s narrations chisel away at the layers of the emperor’s character – one that was as unusual as it was admired. Akbar’s desire to build rapport with subjects, the majority of whom were not of the same faith, formed the bedrock of his vision to bridge differences across spiritual traditions. The culture of interreligious exchange that followed left an indelible mark on India today, where it isn’t uncommon to find shared elements of theology.

Among the chief insights of Father Antonio Monserrate’s observances was the amiability of Akbar towards his courtiers. Memorialized as men of high caliber, they represented diverse religious and academic backgrounds-instrumental to his sulh-i-kul, or policy of tolerance.

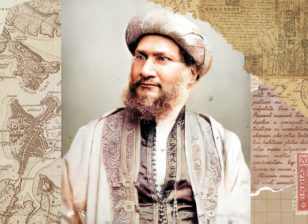

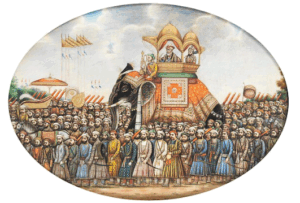

A Rare Rapport: His Diverse Ministry

c.1600 by Manohar Das, Photo Source: Wikimedia Commons

Although the Mughals are claimed to have disenfranchised non-Abrahamic religious groups within the empire, in reality, there were various positions of power which could be exercised, regardless of one’s faith. Most coveted of these were administrative roles, twenty of which were held by Hindus,some of whom were especially endeared by the emperor. Hindu ministers and chieftains were reported to have had intimate communications with Akbar, who entrusted them to the tutelage of his sons. The militarist Raja Man Singh’s family, for example, were members of the Rajput warrior aristocracy. Through several intermarriages, they had forged political and filial ties to the Mughal line of descent. Birbal, a poor Brahmin, is perhaps one of Akbar’s most famous and beloved courtiers – an effervescent character whose death was much grieved. Born Mahesdas, he was affectionately conferred the title Birbal by Akbar himself, who lauded not only his professional credentials but gave him a platform to exercise his repertoire of whimsical talents as a court entertainer.

Public Policy

c.1870-1890, Photo Source: Wikimedia Commons

Although the Mughal court has been implicated in frivolous expenditures at the expense of subjects, it should too be acknowledged that there were administrative reforms enacted to promote enterprise and social justice. Mughal rulers introduced a system based on ownership status and obligations that generated considerable revenue for the empire. The class of Mansabdars (rank holders) were awarded land ownership and development rights in exchange for pledging a certain quota of soldiers in wartime.

Akbar As a Justice

Emperor Akbar also involved himself in protecting the welfare of ordinary citizens, while treating senior officials who abused their trusts with severity. In some accounts, he personally acted as a justice in overseeing these disciplinary actions, highlighting his contempt for political corruption. One source alleged that he, without the strings of sentiment attached, punished one of his most expertised officials for violating a Hindu woman.

Not the Average King

c.1820-1830. Photo source:Wikimedia Commons.

On certain occasions, Akbar could be observed quietly prodding the boundaries of social norm, quarrying stone alongside a group of workmen for his own amusement or accommodating a non-dignitary who wished to converse with him. To patronize the arts, Akbar commissioned the creation of a workshop where craftsmen could ply at their trades. Apart from presiding over art-making, he is also recorded to have dabbled in it himself – details that corroborate Father Monserrate’s remark regarding “his love for any novel object.”

Legacy

c.2025, Photo Source: Wikimedia Commons

Although revisionists have attempted to isolate Akbar’s chapter from the subcontinent’s history, his support of interfaith relations leaves an indelible effect on perceptions of spirituality in India. From recruiting a cabinet of ministers who reflected ideological diversity to welcoming rich discourses on religion, he illustrated that differences, when approached with consideration, can be constructive. Even amid the divisive politics of India today, the kind of society that Akbar cultivated nonetheless reflects the potential of a compassionate tolerance.