A pincer movement aims to stop Christian mission in India

The states of Punjab and Karnataka mobilize to curb evangelical work

By John Dayal

It is a moot question which of the two October developments poses a more potent threat to the Christian mission in India, or at least in states other than Christian strongholds like Kerala, Meghalaya, Mizoram and Nagaland.

The first development is a firman or diktat issued by Sikhism’s top body, the Shrimoni Gurudwara Prabhandhak Committee (SGPC), to curb Christian evangelical activities among the Sikhs in the northern state of Punjab.

The SGPC has sent 150 teams, each comprising seven preachers, to scour the 12,729 villages in the state. This is ostensibly to extend their own pastoral care to the young in Sikh families so that they can resist temptations that may come their way.

This is almost exactly what the Islamic Tabliqi Jamaat does among Muslims, and the Hindu groups such as Vishwa Hindu Parishad and Arya Samaj do among Hindus. Unexceptional, on the face of it.

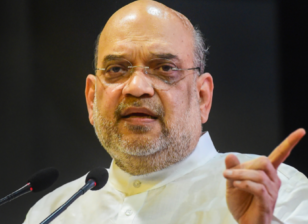

The second development is a decision by the pro-Hindu Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government in the southern state of Karnataka through its backward classes and minorities welfare committee to investigate “official and non-official” Christian missionaries.

The state is expected to join nine other states that have passed laws against “forcible and fraudulent conversions.” The laws were once directed against Christians, and in the last few months against Muslims. Christians are back as targets now.

The Nihangs are in many ways the arbiters of the Sikh way of life in the rural areas of Punjab, where they are both respected and feared

Gulihatti Shekar, the Karnataka state legislative member and BJP leader who advocated the registration of Christian missionaries, said 40 percent of churches in Karnataka are “unofficial and not recognized by the state.”

India does not have a law for registering places of religious worship, with extant regulations covering only properties, management trusts and educational and health institutions.

Various governments in the past have sought to conduct surveys of churches and mission groups and pastors, but all attempts were given up after a few days of publicity and political posturing.

But the state patronage to such political “gossip” did embolden local Hindu nationalist groups to embark on a season of vigilante activity, beating up itinerant pastors, breaking into homes where Christians were praying, or damaging small village prayer halls.

The police watched. The victims were too frightened to insist that the law be obeyed.

The new move is possibly doomed to fail. Archbishop Peter Machado of Bangalore has already protested the survey, saying it was “a dangerous exercise,” more so at a time when the conversion bogey had whipped up anti-religious feelings.

Targeted violence and lynch mobs are all but normalized in India of 2021. With the official machinery ranged firmly against religious minorities in northern Indian states, the SGPC move escalates the threat of harassment and violence targeting Christians in Punjab, just over one percent of the state’s 28 million people concentrated largely in the region around Amritsar and Gurdaspur districts.

Most but not all Punjabi Christians have their roots in the Dalit communities of the state. In fact, when the new chief minister of Punjab, Charanjit Singh Chhani, took office last month, upper-caste politicians accused him of being a closet Christian.

He was the first Dalit to ascend that office in a very caste-conscious state. The chief minister countered the insinuations by organizing the marriage of his son in a gurdwara under Sikh rites in the full glare of national publicity.

By itself, the SGPC move would have been an extraconstitutional irritant. What brings it to attention is the political connection between the committee whose task is administering Sikh religious places in the state and the Akali Dal party which has ruled Punjab for long periods and now holds sway by proxy over the holiest places in the Sikh faith.

As such, decisions of the SGPC carry considerable sway over the community. And in the community are the autonomous groups of armed monks, called Nihangs, who are a law unto themselves. They were in the news at the height of the Covid-19 lockdowns when one of them chopped off the hand of a police sub-inspector who was trying to stop his movements.

This week a group of Nihangs, who had come to join a protest of the country’s farmers at the borders of the national capital Delhi, brutally mutilated and killed a Dalit worker who allegedly touched their holy books. The farmers’ leaders have distanced themselves from the Nihangs.

Sacrilege of the Sikh holy book, Guru Granth Sahib, is as much an issue in the Indian Punjab as damage to the Quran allegedly by Christians in Pakistan, where the penalty under the law is death.

The Nihangs are in many ways the arbiters of the Sikh way of life in the rural areas of Punjab, where they are both respected and feared. They make imposing figures, often mounted on horses, with tall turbans embellished with steel chains of war, armed with steel spears and swords. From personal experience, I can vouch that they are touchy and you cross their path at your own peril. Even Hindu nationalist group Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) is afraid of them, it is said.

Editor Seema Mustafa wrote of them: “Nihangs have always been a volatile force in Punjab. I have seen them closely during the [Jarnail Singh] Bhindranwale-led agitation and visited their deras (monasteries). They follow their own path, are violent and completely out of anyone’s control.”

While Evangelical and Pentecostal pastors are the main victims, Catholic nuns and clergy have faced their share of violence, incarceration and threatened bodily harm.

It does not take a febrile imagination to conjure scenarios where self-appointed guardians of the faith take upon themselves to hunt missionaries either in Punjab or Karnataka. We already have examples from Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh where the RSS has all but taken over from the state in moral and religious policing.

And while Evangelical and Pentecostal pastors are the main victims, Catholic nuns and clergy have faced their share of violence, incarceration and threatened bodily harm.

In the process, the promise of Article 25 of India’s constitution to protect the rights an individual to freely profess, practice and propagate the religion of their choice has gone for a toss.

And while Christians — and now Muslims — are the target, not many seem to realize that the 20 percent or so population of Dalits in the country is effectively denied the freedom to choose the faith they wish to follow.

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, who chaired the committee which wrote the constitution, tested its strength himself in 1956 when he converted to Buddhism, fulfilling a promise he had publicly made that he would not die a Hindu. Tens of thousands of Dalit people converted to Buddhism with him.

In a symbolic gesture, he organized the conversion ceremony not too far from the headquarters of the RSS in the city of Nagpur. The RSS is now trying to appropriate Ambedkar and his legacy as that of his nemesis, Mahatma Gandhi. Those are the ironies of Indian political history.

This article first appeared in ucanews.com