Indian Express : Where does all our hatred come from—Harsh Mander

Harsh Mander writes: The violence in Assam, like that inflicted by lynch mobs, shows normalisation of hatred against communities. It cannot be ascribed to social anomalies.

I am haunted by the lament of two young researchers from Assam, Suraj Gogoi and Nazimuddin Siddique. “We are shaken and frozen”, they say. “Is this the last sky?” The majority of the Indian people have become so inured to brutal public displays of hate violence that when we consume video images of lynching, gangrape and killing of Dalit women, and the flaunting of bigotry by our leaders, we just turn our faces away. What was it then about the recent images from Darrang in Assam — of a man with a lathi shot in his chest trying to defend his home against hundreds of armed security men, and of a young civilian jumping on and kicking the man’s body even as his last breaths cease — that has stirred public outrage?

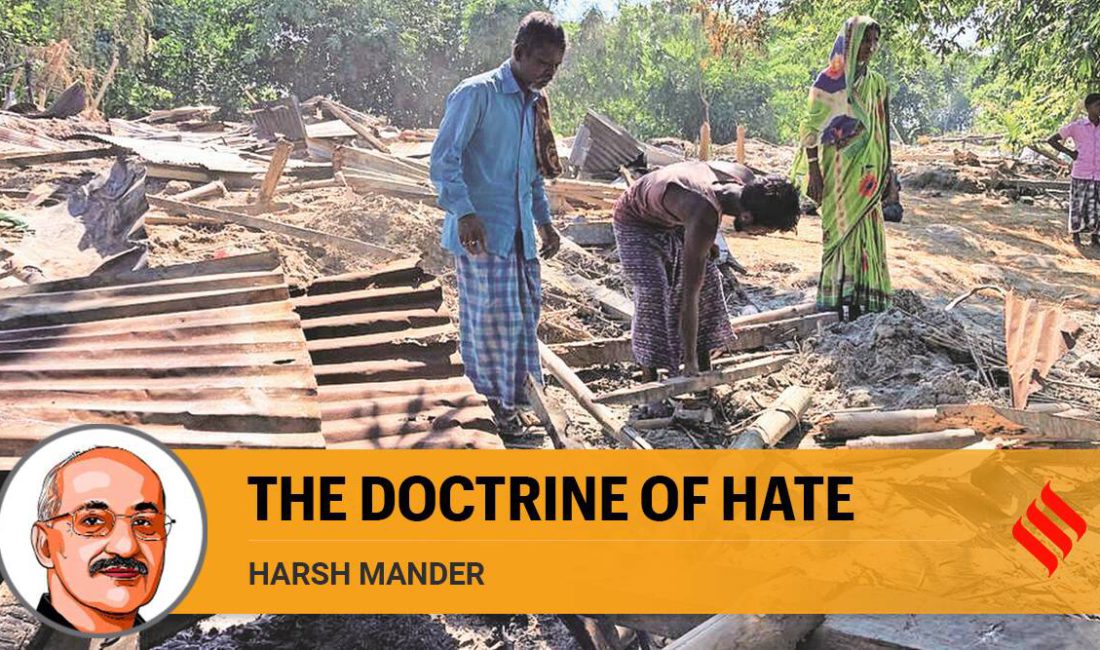

A local activist likened the scene of the Assam village to one “from a war”. There were at least 1,500 armed police and paramilitary soldiers, he said. Eight hundred homes were rapidly razed. A 28-year-old man in a lungi with a stick in his hand ran towards the soldiers in anguish about being rendered landless and homeless. He could easily have been overpowered without firing even a shot. And even if compelled to shoot, the forces are trained to shoot below the waist, so as to temporarily disable but not kill the protester. Instead, they choose to shoot him in the chest.

The village, Dholpur, is one amongst hundreds of riverine islands and riverbanks, vulnerable to erosion every year. On one side is the mighty Brahmaputra and on the other its tributary Nonoi. Landless peasants, mostly of Bengali Muslim origin, have settled here for decades. These are families displaced both by riverine erosion and periodic targeted violence — the most violent incidents took place during the Assam agitation.

Sabita Goswami in Along the Red River describes how in 1983, along with the forgotten massacre of Nellie — the largest post-Independence communal massacre for which not a single person has even been tried, let alone punished — an uncounted number of people were slaughtered in Chaolkhowa Chapori, close to Dholpur.

In the intensely flood-vulnerable riverine islands and banks, large numbers of landless peasants cultivate, under conditions of immense hardship and insecurity, tracts of land for which they have not been issued papers by the state administration. These lands get washed away by floods every few years, and the peasants shift to a new island or river bank each time. In Dholpur, they cultivated three crops every year — corn, jute and peanut — and vegetables like cabbage, brinjal and cauliflower. To call them encroachers is dangerous official fiction.