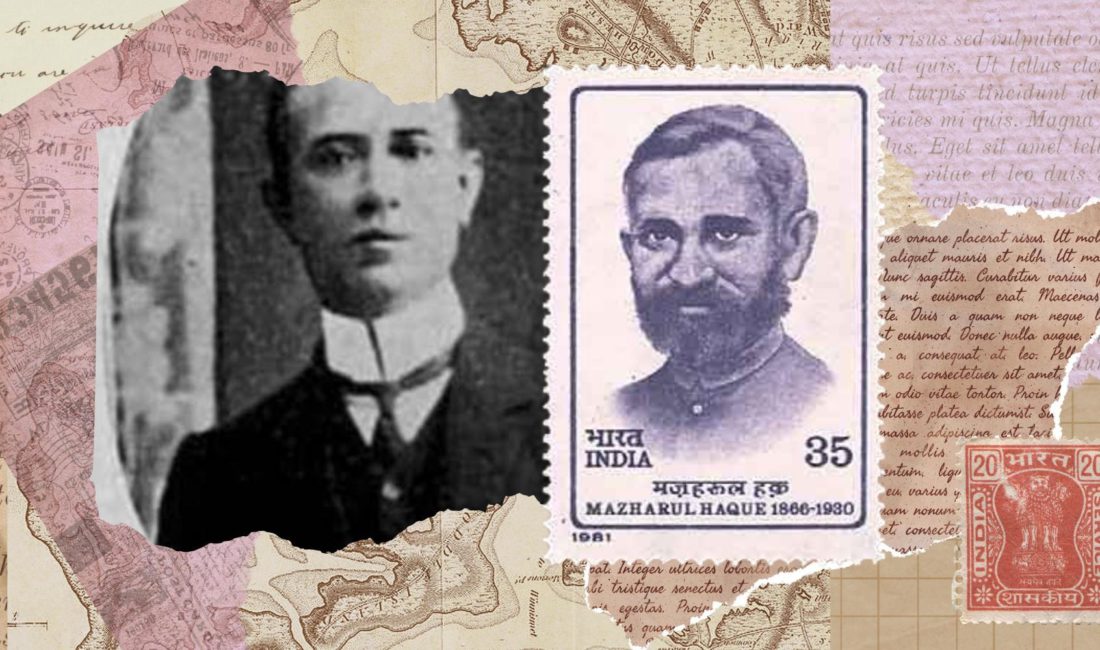

The Freedom Fighter India Forgot: How Maulana Mazharul Haq Helped Shape a Nation

By Afroz Alam Sahil

A figure known for his patriotism, courageous politics, and profound in thought, Maulana Mazharul Haq was a freedom fighter who committed himself to the Indian independence movement, from encouraging Mahatma Gandhi in the early years to supporting him consistently throughout the struggle. Despite being a driving force behind many major programs and policies of the Indian National Congress in Bihar, however, Haq’s contributions are little-known.

Early Life and Education

Maulana Mazharul Haq was born on 22 December 1866 in Behpura (Saran), Bihar, into the family of Sheikh Ahmadullah, a wealthy landowner. He received his early education at home and completed his matriculation from Patna Collegiate School in 1886.

He later went to Lucknow for higher studies, then travelled to England in 1886 to study law. After earning his law degree in 1891, he returned to India and began practicing law in Patna.

After only six months of legal practice, he was appointed in 1892 as a judge in the United Provinces Judicial Service. However, working under the colonial administration conflicted with his morals. Disillusioned by the attitudes of senior officials, he resigned from the position in April 1896. In 1897, he accepted another judicial appointment in Chapra, but once again resigned within six months. He then returned permanently to legal practice, where he established himself as a respected criminal lawyer.

Political Awakening in London

Haq’s involvement in politics began during his student years. While in London, he founded an organization called Anjuman-e-Islamiya, which served as a forum for Indians from diverse religious, regional, and social backgrounds. The association provided a platform for discussions on India’s political and social challenges. The prominent nationalist leader Sachidanand Sinha regularly attended its meetings and later noted that although the organization was nominally Muslim in character, it actively included both Muslims and non-Muslims for many years.

It was through this association in London that Haq first met Mahatma Gandhi, marking the beginning of a relationship that would later play a significant role in India’s freedom movement.

Grassroots Leadership in Bihar

During the severe famine in the Saran district in 1897, Haq organized large-scale relief efforts and helped establish a welfare relief fund, serving as its secretary. His commitment to public service continued at the local level, and in 1903 he was unanimously elected Vice-Chairman of the Chapra Municipality. In this role, he introduced important administrative reforms and significantly improved the municipality’s financial management.

In 1906, Haq was elected Vice-Chairman of the Bihar Congress Committee. Through sustained organizational work, he played a key role in spreading the anti-colonial policies and programmes of the Indian National Congress across different regions of Bihar. His public and political life gained further momentum with the formation of the Bihar Provincial Conference, which he strongly supported. He firmly believed that Bihar should be constituted as a separate province, independent of the Bengal Presidency.

Sikander Manzil and Bihar’s Awakening

In 1908, he moved to Patna, where he emerged as a leading lawyer while deepening his involvement in the national movement. His home, Sikander Manzil on Fraser Road, became a major centre of anti-colonial political activity. As part of the campaign for a separate province for Bihar, he launched a newspaper titled Modern Bihar, although it had a short lifespan. At the 1911 session of the Bihar Provincial Conference held in Gaya, he powerfully articulated the grievances of the people of Bihar under the administration of the Bengal government.

Champion of Hindu–Muslim Unity

Maulana Mazharul Haq was a steadfast advocate of Hindu–Muslim unity and believed that India’s future depended on cooperation between the two communities. He famously stated, “Whether we are Hindus or Muslims, we are all in the same boat; we must either swim together or sink together.” He was among the earliest leaders to oppose the introduction of separate communal constituencies in local bodies. When the British government implemented a communal electoral system in 1909, he emerged as one of its strongest critics.

In December 1909, he was elected to the Imperial Legislative Council, where he consistently opposed the extension of separate electorates at the local level. He argued that the political strength of Muslims should be determined not by legal safeguards but by their active participation in the national movement. Within the council, he also made several important interventions advocating for greater Indian representation in public services.

Political Life

He presided over the Bihar Provincial Congress Committee in 1911 and later over the All-India Muslim League in 1915, reflecting his rare leadership across political and religious platforms. He played a crucial role in facilitating the historic agreement between the Indian National Congress and the Muslim League at the Lucknow Session of 1916.

In the same year, he actively supported the Home Rule Movement led by Annie Besant and Bal Gangadhar Tilak. He established a branch of the Home Rule League in Bihar and served as its president. Through extensive tours and public meetings across Bihar and Orissa, he popularized the demand for Swaraj (self-rule) and helped train and mobilize a new generation of freedom fighters.

In 1917, when Mahatma Gandhi travelled to Champaran to investigate the plight of indigo farmers, he first arrived in Patna. Initially uncertain about proceeding, Gandhi reconsidered after meeting Haq, who made all the necessary arrangements for Gandhi’s visit to Champaran. This intervention proved decisive, as the Champaran Satyagraha was Gandhi’s first major mass movement in India, marking a turning point in the national struggle and helping establish Gandhi’s global reputation as a leader of nonviolent resistance.

In 1919, Haq publicly renounced Western dress by burning his European clothes and adopted traditional attire as a symbol of cultural and political resistance. He came to be known by the honorific titles Desh Bhushan (“Jewel of the Nation”) and Faqir, reflecting both his national stature and personal simplicity. He donated his Patna residence, Sadaqat Ashram, which later became the headquarters of the Bihar Congress, to the Indian National Congress. From this ashram, he also published a weekly newspaper titled The Motherland.

During the Khilafat and Non-Cooperation Movements, his contribution to building political awareness and organizing mass participation in Bihar was exceptional. At Mahatma Gandhi’s request, he gave up his highly successful legal practice and devoted himself entirely to the national cause. He played an active role in establishing national madrasas and founded the Bihar Vidyapith (National University) to promote indigenous education.

Haq devoted himself entirely to the Khilafat and Non-Cooperation Movements. Fluent in Turkish, he had established contacts with leading political figures in Turkey even before the Khilafat Movement began in India. As an advocate of Pan-Islamic solidarity, his active participation in the Khilafat Movement was a natural extension of his political beliefs.

Soon after the Khilafat Movement gained momentum in India, the British colonial government introduced the Rowlatt Act, which allowed for repressive measures against political dissent. Mazharul Haq strongly opposed this legislation and took a firm stand on behalf of the Indian National Congress. In March 1920, a delegation led by Maulana Muhammad Ali Jauhar travelled to London to meet the British Prime Minister and seek permission from the Supreme Council of the Peace Conference to present their demands. The request was rejected, and Prime Minister David Lloyd George made it clear that the Ottoman Empire would not be allowed to retain territories beyond Turkey. This decision deeply hurt public sentiment in India.

In response, Mahatma Gandhi announced that if the post-war settlement with Turkey failed to respect the sentiments of Indian Muslims, he would launch a nationwide Non-Cooperation Movement. This declaration marked the formal beginning of the Non-Cooperation Movement in India. Mazharul Haq emerged as one of its leading organizers in Bihar. He travelled extensively across the country, particularly throughout Bihar and Orissa, addressing public meetings and mobilizing people in support of non-cooperation with colonial rule.

From 1924 to 1927, he served as the first Chairman of the Saran District Board, where he once again demonstrated his administrative vision. He opposed the Audit Bill and, despite serious financial constraints, introduced compulsory primary education in the district. In November 1926, he was defeated in the elections to the local Legislative Council. His political positions, which some members of his own community viewed as overly accommodating toward Hindus, led to a loss of support among Muslim voters, while Hindu voters did not fully accept him as their leader.

Deeply affected by this political setback, Mazharul Haq withdrew from active politics. Despite appeals from Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, he declined the presidency of the Indian National Congress and chose a life of seclusion at his residence, Ashiana, in the village of Faridpur in the Saran district.

Death and Legacy

During this period of seclusion, Maulana Mazharul Haq suffered a stroke on 27 December 1929. After several days of illness, he passed away on 2 January 1930.

Mahatma Gandhi paid a moving tribute to him in Young India on 9 January 1930, writing: “Mazharul Haq was a great patriot, a good Mussalman and a philosopher. Fond of ease and luxury, when Non-co-operation came he threw them off as we throw superfluous scales off the skin. He grew as fond of the ascetic life as he was of princely life. Growing weary of our dissentions, he lived in retirement, doing such unseen services as he could, and praying for the best. He was fearless both in speech and action. The Sadakat Ashram near Patna is a fruit of his constructive labours. Though he did not live in it for long as he had intended, his conception of the Ashram made it possible for the Bihar Vidyapith to find a permanent habitation. It may yet prove a cement to bind the two communities together. Such a man would be missed at all times; he will be the more missed at this juncture in the history of the country…”

Maulana Mazharul Haq’s legacy endures through his lifelong commitment to national unity, social reform, and selfless service. Though often underrepresented in mainstream historical narratives, his contributions played a vital role in shaping India’s freedom struggle and promoting harmony across communities.