Thousands of mosques targeted as Hindu nationalists try to rewrite India’s history

Shamsi Jama Masjid, an 800-year-old mosque in Uttar Pradesh, is the latest flashpoint in a dispute that could eventually turn violent.

In a small, darkened office in Budaun, where dusty legal books line the walls, two lawyers have fallen into a squabble. VP Singh and his taller associate BP Singh – no relation – are discussing Shamsi Jama Masjid, the mosque that has stood in this small town in Uttar Pradesh for 800 years.

According to the lawyers, this grand white-domed mosque, one of the largest and oldest in India, is not a mosque at all. “No no, this is a Hindu temple,” asserted BP Singh. “It’s a very holy place for Hindus.”

Records dating back to 1856 make reference to the working mosque, and according to local Muslims, they have been praying there undisturbed since it was built by Shamsuddin Iltutmish, a Muslim king, in 1223. The Singhs however, have a different version of events. In July, they filed a court case on behalf of a local Hindu farmer – and backed by the rightwing Hindu nationalist party Akhil Bharat Hindu Mahasabha (ABHM) – alleging that Shamsi Jama Masjid is not a mosque but an “illegal structure” built on a destroyed 10th-century Hindu temple for the god Shiva. Their petition states that Hindus have rightful ownership of the land and should be able to pray there.

Except, the two bickering lawyers can’t quite agree on the historical facts. BP Singh initially claimed that the original Hindu temple was destroyed by a Muslim tyrant king – but then VP Singh contradicts him.

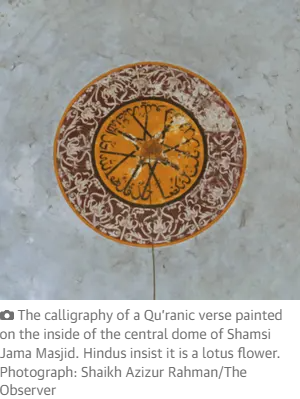

“Not destroyed, altered,” said VP Singh. “Most of the original Hindu temple is still there.” They claim as evidence a lotus flower painted on the inside of the mosque dome. But when the Observer was given access to the mosque, there was no such Hindu motif, and instead it was the calligraphy of a Qur’anic verse. There was also no sign of an alleged “hidden locked room filled with Hindu idols” in the mosque, which VP Singh claimed he had seen in the 1970s as a child. Instead, the room in question was a store cupboard, filled with cleaning materials and prayer mats.

The pair also could not settle on exactly when Shamsi Jama Masjid, which they refuse to call a mosque, began to be used by Muslims for prayer five times a day as it is today. After BP Singh stated that Muslims were praying there up till the 1800s, VP Singh leaned over to mutter quietly to his associate: “No no don’t say that, don’t say that.”

More loudly, VP Singh then proclaimed: “Actually no this wasn’t a mosque, it was never used for namaz [Muslim prayer] until recently when the Muslims forcibly occupied it and tried to convert it into a mosque.” They claimed to have “proof” but were unable to find it.

“When the Muslims ruled, we Hindus were all persecuted, we were killed and tortured,” added BP Singh. “Now we are taking back what is rightfully ours.”

The case has been met by puzzlement from local Muslims, who are contesting it in court. “How can you claim this is not a mosque?,” said Anwer Alam, legal counsel for the mosque committee, pointing up to the imposing white domes. “No Hindu has ever prayed at this mosque since its inception 800 years ago. This suit has no legal grounds.”

But those behind the case say Budaun is just the beginning. “We have a list of about 3,000 that we have decided to reclaim legally,” said Sanjay Hariyana, a state spokesperson for ABHM.

Since 2014, when the Bharatiya Janata party (BJP) government came to power, India’s 200 million minority Muslims say they have been subjected to persecution, violence and state-sponsored discrimination. Under the Hindutva (Hindu nationalist) agenda – which aims to establish India as a Hindu nation, rather than a secular state – Muslim civilians, activists and journalists have been routinely targeted, Muslim businesses boycotted and Islamophobic rhetoric used by BJP leaders, while lynching of Muslims has been on the rise.

Mosques have begun to be caught up in a wide-ranging project under the BJP to rewrite India’s history according to Hindutva ideology. The version of history now propagated by BJP leaders, government-backed historians and school curriculums is that of an ancient Hindu nation oppressed and persecuted for hundreds of years by ruthless Muslim invaders, particularly the Islamic Mughal empire that ruled from the 16th to the 19th century.

The alleged destruction of Hindu temples to build mosques has been central to this narrative. In May, a senior BJP leader claimed that Mughals had destroyed 36,000 Hindu temples and they would “reclaim all those temples one by one”.

But Richard Eaton, a professor of Indian history at the University of Arizona, said there was no historical evidence for this, with Mughals thought to have torn down only about two dozen temples. “Claims of many thousands of such instances are outlandish, irresponsible and without foundation,” he said.

Historians have accused the BJP of not only rewriting, but “inventing” India’s history in their own image. Syed Ali Nadeem Rezavi, a professor of Mughal history at Aligarh Muslim University, described the BJP’s polarized version of Indian history as “fantasy, nothing more than fiction” invented to serve their political agenda. “The history of India is being painted as a black and white narrative of Hindus versus Muslims,” said Rezavi. “But it was never so.”

Yet Indian historians whose work contradicts this version of history, or who have spoken out, have found themselves sidelined, penalized or ousted from government bodies and academic institutions which rely on government funding.

Rezavi is one of the few historians in India who still dare to speak; many approached by the Observer declined, citing fears over their jobs or their safety. Foreign historians have also been targeted. Audrey Truschke, a history professor at Rutgers University in the US, has faced death threats, allegedly from Hindu rightwing groups, for her work on Mughals.

Rezavi likened the attacks and silencing of historians and scholars to the targeting of academics in Nazi Germany. “A large number of historians are afraid to speak up openly,” he said. “I have been a victim of discrimination and persecution because of speaking up. But show me one Indian historian worth his salt who is with the government? There is not one.”

As the impetus to avenge and reclaim India’s history for Hindus has gained traction, dozens of petitions have been filed by right-wing Hindu groups against mosques across the country. India has a law which explicitly protects places of worship from being disputed post-1947 but judges are allowing cases. Even India’s most famous monument, the Taj Mahal, which was built by the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan, has not escaped litigation, and a case – widely derided by historians – was filed alleging it was originally a Hindu temple with locked rooms of Hindu relics. Alok Vats, a senior BJP leader, said the party had “no role” in the lawsuits but that these groups were “seeking to do exactly what the Hindu community wants”.

The cases have been further galvanised by a 2019 supreme court ruling which handed over Babri Masjid, a 16th-century mosque in the Uttar Pradesh town of Ayodhya, to Hindus after they claimed it was the birthplace of their god, Lord Ram. In 1992, the mosque was torn down by a rightwing Hindu mob, an incident many fear could now be repeated with the escalating number of disputed mosques. This month, a mosque in the city of Gurgaon was violently attacked by a mob of about 200, while in the state of Karnataka a Hindu crowd barged into a madrassa, placed a Hindu idol inside and performed a prayer.

In Mathura, a city in Uttar Pradesh, Shahi Eidgah mosque, built by the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb in 1670, is now facing 12 lawsuits claiming it is built on the birthplace of the Hindu god Lord Krishna and ruins of a Hindu temple

Muslims are fighting the case but in a city that has long prided itself on communal harmony, Hindus are also among those opposing the dispute. Mahesh Pathak, chief of an all-India body of Hindu priests, said: “They say a temple was demolished by Aurangzeb but that is long in the past. This is all political, not religious.”

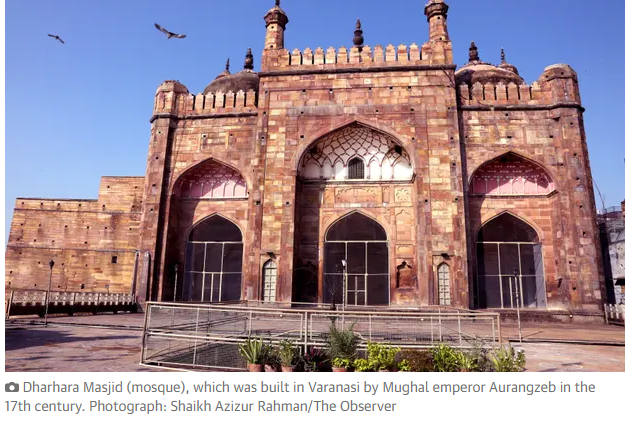

However, it is the legal dispute over the 17th-century Gyanvapi mosque, constructed by Aurangzeb in the holy city of Varanasi, which is seen by many as the crucial case that could decide the fate of mosques across India.

What began as one petition filed by five Hindu women in 2021, seeking access to pray inside the mosque which they claim is built on a destroyed ancient Shiva temple, has ballooned to 15 separate petitions, with many calling for the mosque to be torn down and a temple built in its place. Muslims still pray at Gyanvapi five times a day, though it is surrounded with prison-like security, including concrete barriers, barbed wire and a heavy police presence.

“This is a Hindu property, there is nothing connected to Muslims on this land,” said Anand Singh, the regional leader of Bajrang Dal, a Hindu nationalist militant organisation that has been financially and logistically supporting the Hindu legal case. “It is a Shiva temple and the current structure is an illegal structure. This is a very important moment for Hindus reclaiming their history and ancient glory,” he said.

One of the petitioners, Sita Sahoo, 46, admitted she had never been inside Gyanvapi but was sure that idols of Hindu deities were buried beneath the mosque, which she referred to only as a Shiva temple. “This is a holy place for all Hindus. We should have free daily access to this place for darshan [religious visits] and puja [prayer],” said Sahoo. During a hearing for the petition this month, four of the women stood outside the courtroom singing religious songs in front of dozens of eager television cameras.

The situation has become more febrile since May when lawyers for the Hindu side claimed to have “found” a religious icon of Lord Shiva, known as a Shivling, inside the mosque during a court-ordered survey.

Syed Mohammed Yaseen, 75, who has been the caretaker of Gyanvapi mosque for more than 30 years, said all these claims of Hindu iconography, idols and prayer inside the mosque were “unbelievable” and “completely untrue”. “Hindus have never prayed inside the mosque in its 350-year history,” he said.

He and dozens of other regulars at the mosque said the alleged Shivling was in fact part of a broken fountain that has been installed at the mosque for about 70 years, pointing out that it has a hole through the middle for water, something never seen on a Shivling icon. It has yet to be examined by judges or experts, but the area has been sealed by the courts. The BJP told the Observer that it had no connection to the lawsuit but after the discovery of the alleged Shivling, the BJP deputy chief minister of Uttar Pradesh declared that “Lord Shiva has appeared where we were looking for him”.

But like many Muslims in Varanasi, Yaseen feared that in the current political climate, the case was already decided against them. “So far we haven’t seen any part of this trial to be fair,” he said. “This is a case which is being filed by Hindus and decided by Hindus, everybody is on their side: investigators, judiciary, government. I tried my best to appoint a Hindu lawyer but no Hindu lawyer would fight for us.”

Abdul Batin Nomani, the grand mufti of Varanasi, who oversees all mosques in the city, was equally pessimistic. “We know this mosque is just the beginning,” he said “But if they hand it to the Hindus, there will be bloodshed.”

(Hannah Ellis-Petersen is The Guardian’s South Asia correspondent)

This article originally posted in The Guardian