Maulana Abul Kalam Azad: The Scholar Who Shaped India’s Mind and Soul

By Afroz Alam Sahil

After independence, Partition divided India and Pakistan, tensions between religious communities in Delhi increased, and Mahatma Gandhi began a fast on January 12, 1948, to promote peace and communal harmony.

After five days, Gandhi’s health began to deteriorate. His kidneys were not functioning properly, but he remained determined not to end his fast. Several national leaders tried to persuade him to stop, but he refused. Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, deeply concerned about Gandhi’s condition, suggested he at least drink some diluted seasonal juice, but Gandhi declined. Finally, at Azad’s urging, he agreed to take a little lemon juice under specific conditions.

On January 17, 1948, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad addressed a gathering of over 300,000 people in Delhi. During his speech, he shared that he had recently met Mahatma Gandhi to discuss the conditions under which Gandhi would agree to end his fast. Gandhi had set seven conditions, insisting that they be formally endorsed by responsible leaders who could guarantee their full implementation—without offering any false assurances.

Among Gandhi’s key conditions were the following:

- Muslims should have full freedom to visit the shrine of Khwaja Qutubuddin Bakhtiar Kaki in Mehrauli, and no obstacles should be placed in the way of the upcoming Urs (annual commemoration) to be held there within the week.

- All mosques in Delhi that had been occupied or converted after the riots should be returned to the Muslim community.

- Muslims should be allowed to move freely in their former neighborhoods without fear or restriction.

- It must be ensured that Muslims can travel safely by train.

Gandhi’s conditions focused on restoring security, religious freedom, and mutual trust. Maulana Azad presented these points with great conviction, and people across India took his words to heart.

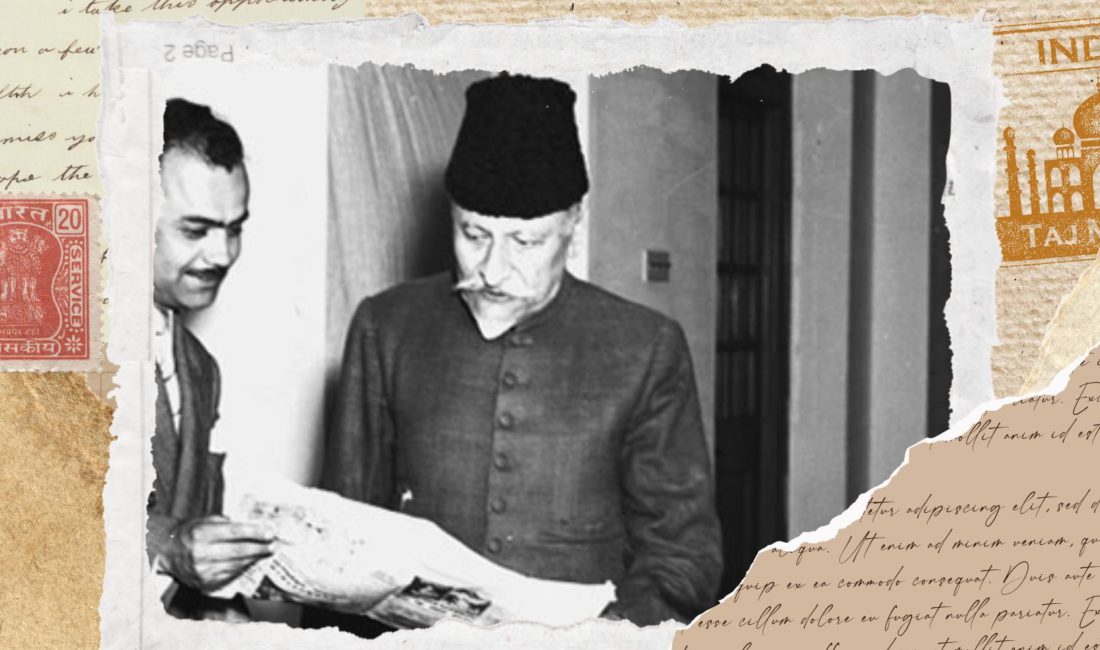

The following day, on January 18, more than a hundred leaders from various political and social organizations in Delhi — including representatives of Hindu Mahasabha, RSS, and Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind — met Gandhi and signed a pledge to uphold these commitments. At 12:15 p.m., Maulana Azad offered Gandhi a glass of juice, marking the end of his fast.

Tragically, despite Gandhi’s efforts for peace, only days later he was assassinated. After his death, some groups resumed the very activities Gandhi had opposed, undermining the spirit of reconciliation he had sought to achieve.

A Master of Language and Speech

Maulana Abul Kalam Azad was naturally gifted with all the qualities of a great orator. His father, Maulana Khairuddin, was a respected religious scholar and Sufi who wrote several works in Arabic and Persian. He also had a wide circle of disciples whom he regularly guided through teaching and spiritual instruction. On Fridays, he often delivered sermons before the congregational prayers at the Jamia Masjid (Masjid Nakhoda) in Calcutta.

Growing up in such an environment, young Abul Kalam Azad was deeply influenced by his father’s eloquence and public speaking. It is no surprise that from an early age, he dreamed of becoming a speaker himself. His elder sister, Fatima Begum, confirmed this in an article published in Aajkal magazine in September 1959. She recalled:

“Sometimes he would stand on a high spot in the house, gather all of us sisters around him, and say, ‘Clap your hands and imagine that thousands of people are standing before me, listening to my speech and applauding.’ I would say, ‘Brother, there’s no one here except the two of us—how can we imagine thousands?’ He would reply, ‘That’s the fun of the game; this is how games are played.’”

Even as a child, Maulana Azad’s imagination and passion for public speaking foreshadowed the eloquence and leadership that would later make him one of India’s most powerful voices.

He also had a lifelong passion for books and learning, beginning from when he was just ten years old. He once wrote, “At the age of ten, I was so fond of books that I used to save the money I received for breakfast and spend it on buying books.”

Even while deeply engaged in political life, Azad never allowed his intellectual pursuits to fade. His commitment to knowledge remained steadfast until his final days. Alongside his scholarship, he carried a strong sense of social responsibility and an unwavering dedication to his country. The pursuit of knowledge was, for him, not a pastime but a lifelong mission.

Throughout his life, Maulana Azad authored several significant works that continue to hold immense value. Among them, Tarjuman-ul-Qur’an and India Wins Freedom are especially renowned. His other notable writings, such as Tazkirah and Ghubar-e-Khatir, stand as enduring contributions to Urdu literature and philosophy.

Revolutionary Journalism

From an early age, Maulana Azad showed a deep interest in both writing and public speaking. Influenced by his intellectual and literary surroundings, he began composing poetry and prose at the age of ten. His early writings appeared in various journals and magazines in Calcutta and beyond. Yet, young Azad was not content with merely contributing—he wanted to publish his own magazine.

At just ten or eleven years old, in 1899, he launched a small publication called Nairang-e-Alam, which ran for about eight issues and featured poems by young writers.

Azad’s formal entry into journalism came in 1900 when, at the age of twelve, he became the editor of the weekly Al Misbah. A few years later, in 1903, he started a monthly journal titled Lisan-us-Sidq, which quickly gained recognition for its thoughtful content and literary quality.

By the time he was twenty, Azad had traveled through parts of West Asia, where he met several Arab and Turkish revolutionaries striving for their nations’ independence. Deeply inspired by their ideals, he returned to India with a renewed sense of purpose and began to engage in political work.

With the goal of awakening political and national consciousness among Indians, he launched the weekly newspaper Al-Hilal in Calcutta on July 13, 1912. The publication quickly became influential, known for its bold criticism of British colonial rule and for addressing not only political matters but also social, scientific, historical, and literary topics relevant to the Muslim community and Indian society as a whole.

The British authorities, alarmed by its outspoken tone, imposed a fine of ten thousand rupees on Al-Hilal and eventually shut it down when Azad refused to pay. Undeterred, he soon established another newspaper, Al-Balagh. While it contained fewer overtly political articles, Al-Balaagh continued to promote education, literature, history, religion, and social reform, carrying forward Maulana Azad’s vision of journalism as a force for enlightenment and national awakening.

The Khilafat Movement

In 1916, the British government placed Maulana Abul Kalam Azad under house arrest in Ranchi. After nearly four years of confinement, he was released on December 27, 1919. Shortly after his release, on January 18, 1920, he met Mahatma Gandhi—a meeting that marked the beginning of his deep involvement with the Indian National Congress and the broader struggle for India’s independence.

When the Khilafat Movement began, Maulana Azad joined it wholeheartedly and soon emerged as one of its most prominent leaders. He traveled extensively across India, inspiring people through his powerful speeches and persuasive writings. His oratory and journalism helped awaken political consciousness among Muslims and promoted unity across religious lines. One of the significant outcomes of the Khilafat Movement was its role in strengthening the idea of Hindu-Muslim unity—an ideal that Maulana Azad championed passionately.

During the movement, on December 10, 1921, Maulana Azad was arrested in Calcutta and sentenced to one year of imprisonment. He was released on January 6, 1923. Later that year, he was chosen to preside over a special session of the Indian National Congress, originally planned for Bombay in August but eventually held in Delhi on September 5, 1923. At this session, Maulana Azad—then only 35 years old—became one of the youngest Presidents in the history of the Indian National Congress.

Early Life and Family Roots

Maulana Abul Kalam Muhiuddin Ahmed Azad was born on November 11, 1888, in Mecca (now part of Saudi Arabia). About eight years later, his family returned to India and settled in Calcutta (now Kolkata). His early education followed traditional lines and was supervised by his father. After mastering Arabic and Persian, he went on to study philosophy and mathematics.

Maulana Azad was a man of many talents — a scholar, writer, poet, orator, and educator, as well as a respected interpreter of Islam. Yet, he is best remembered as a visionary political leader and a key figure in India’s freedom movement.

Maulana Abul Kalam Azad passed away on February 22, 1958. Paying tribute to him in the Lok Sabha (India’s Parliament), Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru said: “There are many great people in our country and there will be many more in the future, but the unique and special kind of greatness that Maulana Azad possessed is rarely seen in India or anywhere else.”

In recognition of his lifelong commitment to education and learning, the Government of India declared his birthday, November 11, as National Education Day in 2008.